Over the last couple of months, we stepped back from the edge of manufacturing to apply some TLC to Far Away: Corporation Espionage. The main reason was to wait for some relief from the tariff chaos. But the lure of “more time” is undeniable. Every playtest turns up new issues, since the nature of the exercise invites feedback. Amateur game designers often preach that there is no such thing as too much testing, but you can easily fail into a trap of never publishing in the name of quality. It’s a trap that punishes our backers.

To sate our loyal fans, we are revving back up the production engines and talking to our manufacturer about die cuts, inlays, and the other stuff you never concern yourselves with when printing paper test copies. To stop iterating on the content carries inherent risks: a rule is unclear, some strategy is too dominant, a conflux of random outcomes creates a horrible situation for players, or the game just isn’t fun enough. Those are the typical risks one expects. Everyone who habitually crowdfunds board games anticipates some degree of this (which doesn’t excuse it or those folks happy when it happens). However, there is a set of quality issues that may crop up which feel more baffling. In what you could either interpret as industry transparency or a preemptive mea cupla, I want to go over some potential problems and their causes.

The backend of board game development is more complicated than one might think. The FA:CE manual isn’t just a Word doc. It’s an InDesign file with 5 layers, 81 links to other files, 10 paragraph styles, and numerous textboxes, graphics, and other bits. Editing text on one page can cause an unexpected shift elsewhere. There’s not the same spelling and grammar support you might be used to in other editors (and linking the content has other concerns). Adjusting the order in a deck of cards causes the wrong image to be linked to in the manual. And that’s just the manual. The entire FA:CE folder contains over 80 folders and about 2,000 files. There’s skill in ensuring rules stay properly documented across mission cards, gear cards, the mission booklet, the rule book, and all the content of the base game. All this makes editing a recursive problem – you can’t “finish” one piece because it’s all interconnected.

Ultimately, the digital stuff is all under our control. What’s not is the physical production. There’s no way to recreate the exact factory settings; any attempt at a prototype will vary in materials and color. The factory itself won’t be able to make a perfectly accurate prototype because the printers are different for one-offs and some components, like dice, can’t necessarily be made individually. For a company our size, we have a series of emails and file transfers with the manufacturer, then get a proof copy to approve. When we did this for Far Away, they provided cubes and dice in the right size, but were either different colors or unfinished (not polished with smooth sides and round corners). Each proof copy costs hundreds of dollars and adds weeks to the production timeline; it’s not impossible to get another one, but it’s not something to plan for. The expectation is to correct minor errors without another proof, which can lead to the issues listed in the earlier section. I have to assume these last-minute fixes are responsible for the most egregious errors in games.

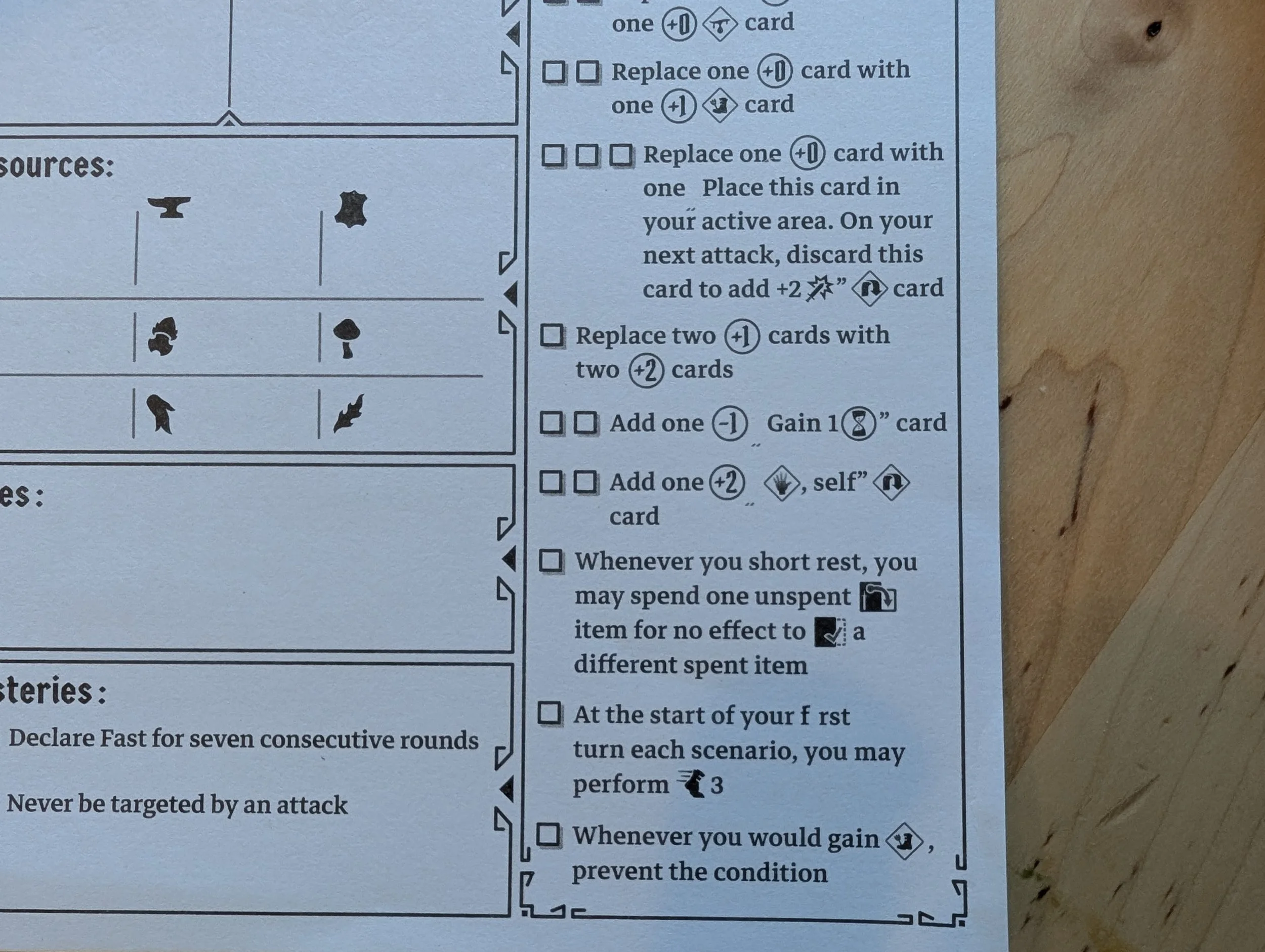

Even $13,000,000 can’t buy enough editorial support. This Frosthaven Blinkblade character sheet is probably an example of where some last-minute edit caused the inverted quotation mark to replace some vital text. And the other quotation mark issue. And for “first” to be misspelled…

The most terrifying and least controllable aspect of production is the state of the world when we start fulfilling the game. Tariffs, shipping costs, taxes, EU import regulations, sanctions, and wars are all subject to change in the weeks and months after we send the files to our manufacturer and when we put games in boxes. This is the stuff that has the most impact on the business and the ultimate delivery of the game. It’s also the stuff that is the most removed from game design – from the desire to provide a unique experience to someone sitting at a table opening a box of cardboard and using their imagination to transform it into an alien world. The world is becoming increasingly hostile to small businesses. Hopefully, whatever changes between now and packing games for people doesn’t cost us so much that FA:CE is the last game we make.

Luckily, the stress of this final phase is mitigated by the relief of shipping and the satisfaction of players finally getting the game. Hopefully none of the issues mentioned in this blog comes to pass. Realistically, we’re prepared to hear about all our typos and respond to your questions on BGG.